Why are computers still so dumb at the Game of Go? Don't they want $1,000,000 ?

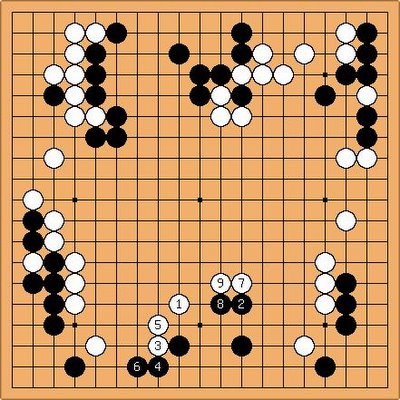

After move 71 of a Go game played from 16-18 July 1669 between Dosaku (white stones) and Doetsu. Many consider Dosaku to have been the greatest of all Go players, although he eventually lost this game.

Go, which has been played for 4000 years, occupies a place in eastern Asia comparable to chess in Europe and the Americas. Experts at both games tend to consider Go the more difficult. In Japan, Go is played everywhere, but chess has very few players and the Japan Chess Association is a very small and somewhat lonely place. Its longtime secretary championed Bobby Fischer during his detention in Japan, married him, and moved to Iceland with him. Go is also common in Korea (called baduk), Vietnam and China (called wei-chi or weiqi).

World-champion-level computer chess has been a Solved Problem since Deep Blue, a descendant of Deep Thought, a graduate-school engineering project, defeated world champion Gary Kasparov in a match in 1997. Technically, chess computers rely on brute-force computation, analyzing millions of possible sequences of moves within the time permitted for human-human competition.

Despite going on two decades of intense research, computers remain largely incompetent at defeating expert human players at Go; skilled children commonly wipe the best Go computers all over the board. Go handhelds and software offer low- and mid-ranked amateurs and students a fairly challenging game, but no software or dedicated hardware has yet come close to defeating a Go master.

As chess was before it was solved, computer Go is considered to be an extremely important problem in the field of Artificial Intelligence. If nothing else, it spurs researchers into novel areas of problem-solving, some of which will almost certainly be valuable for other problems or classes of problems, some of which might even have practical applications. But if Our Silicon Friends are growing smarter and smarter, computer Go remains one of their most stubborn obstacles. We're better than this than they are, and barring some wholly unanticipated breakthrough, it seems we're going to stay better at Go for a long time.

Another incentive is that a Taiwanese businessman named Ing offered, before his death, a U$1,000,000 prize to the first computer which could defeat a human Go master in a tournament. The Ing prize is apparently still waiting to be won.

Hypnotically beautiful patterns of stones often flower during a game, and some players say they often feel torn between winning and cooperating with the opponent to grow a beautiful pattern -- which could be opposite goals.

Players also love the feel of putting a stone on the board, and the click noise it makes; you can buy cheap plastic stones, but players pay a lot for polished oyster shell and stone stones. Players also pay up to $50,000 for a board, carved from a single tree specially grown for just that purpose. (But you can buy a board and stones for $45).

Samarkand also has a Java applet called JiGo which allows you to watch any game from a large database re-played one move at a time. Or you can click the [Skip To End] button and see the final often exquisite pattern.

(Chess websites also let you replay famous games one move at a time.)

A nickname for Go is "Rotten Axe Handle." A woodsman with a brand-new axe paused to watch two Go masters play a game by the side of the road, and became fascinated with the game. When the masters finished, the woodsman looked at his axe and noticed that the handle had completely rotted away. (Go games can last a very long time.)

As chess has in the West, Go has infected Asian art and literature for centuries. Nobel Literature laureate Kawabata Yasunari's most famous and translated novel is "The Master of Go" (1951), original title "Meijin." It is a fictionalized retelling of a championship tournament he had covered as a reporter.

Two players. One gets a bowl of white stones, the other a bowl of black stones. White places the first stone on an intersection of a 19 x 19 grid of lines. Thereafter, according to a few simple rules, each player places one stone on a vacant intersection (although a player may choose to pass a turn). The object is to surround and occupy more intersections than the opponent.

Life and Death is a central question to determine which color will force an inevitable win in the fight for territory in an evolving associated community of stones -- whose stones will live, whose will die (i.e., be removed from the board)? A good player should know when a position is lost no matter what the player does, and move to a more promising area of the board.

There is a handicap system by which the weaker player begins the game with from one to nine stones already placed on intersections with round dots.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home