The Barmecide's Feast

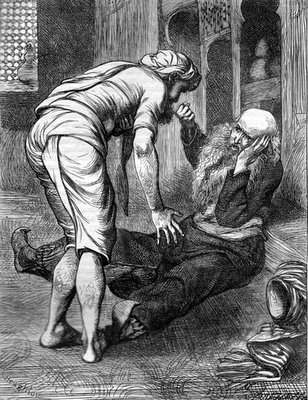

Shakashik knocks down the Barmecide

For fifteen years, the emergency winter homeless shelter of Northampton Massachusetts USA has opened its doors at suppertime beginning on Halloween night, and serves a hot meal, provides a warm bed, and a cold breakfast every date until May Day, after which our homeless guests -- we have beds and make stew or pasta each night for about twenty-two men, women and throw-away teenagers -- are invited to spend the rest of spring, summer, and the first chilly autumn months sleeping and dining al fresco, rough, and by their own wits.

While the shelter is open, only some brief, rare freak of warm weather leaves empty beds; far more regularly, we must turn away cold and hungry Guest No. 23, 24, 25, 26 and beyond. Usually each bitter winter somewhere within a 20-mile radius of Northampton, a homeless man will be found in the morning dead of exposure from sleeping outdoors, in the woods, in a deserted building without heat, by the railroad tracks. We live in terror it will be someone we were forced to turn away because of Fire Code restrictions.

In the past few years, the shelter has been in the basement of Northampton Friends Meeting House -- known more familiarly by the community as The Quakers. There may someday be a better or more appropriate place for our town's homeless shelter, but in the Only World I Know, a World whose priorities are greed and war, the Basement of Friends Meeting House (previously the architecturally distinctive Elks Club), is a fine, realistic, thoughtful place

all watched over by Friends of loving grace

(with apologies to Richard Brautigan).

I am privileged now and then to cook for the shelter guests. I cook during the day in my kitchen at home, and then schlep the chow downtown to the shelter in my pickup truck. (I am the famous Saint Bob of the Truck.) When I park the truck, the guests have not yet been admitted, the shelter is closed all day, so they wait outside, lined up against the wall in the dark, smoke 'em if they got 'em -- many of them are military veterans from America's many previous wars -- and help me with the kettles and the doors.

If they were not so sick, so desperate, so exhausted, so hopeless, so frightened each night after dinner, I might be tempted to try to tell them a story. But they are all these things, and more sad things that I do not know of, and I must content myself to a Cook's Reward -- to know only that their bellies have been filled, and they will be warm and safe when shortly they lie down and the dormitory lights are turned off. (But a Cook's Reward is a wonderful Reward.)

So I will tell you a story, a story from Alf Layla iwa Layla, the Thousand and One Nights, or the Arabian Nights, and I very much hope you like it. If you like it, please Leave A Comment. It's much harder to know if you like what I write than it is to know if people who eat my food like it. Smile, pat your bellies, fart a little, Leave A Comment.

{ [ ( o ) ] }

The Barmecide's Feast

told this time by Bob Merkin

Copyright (c) 2005 All rights reserved

Copyright (c) 2005 All rights reserved

Once long ago in Baghdad, in the times of the great and wise Caliph, a vagrant -- what we would call today, My Child, a homeless man or a street person -- wandered the streets of the prosperous quarter hoping for a miracle which would add something sweet and solid to his empty, gnawing belly. Two days earlier he had eaten a thrown-away apple rotten and swarmed with tiny flies; that was his belly's last memory of sustenance.

In Paradise we will be vouchsafed to know why Allah, Blessed be He, the Creator of all Bounty, who marbled most hearts with Generosity and Charity, has seen fit to put so many hungry mouths in our midst in prosperous times and places, but whilst we dwell on this Earth, Dear Child, this must remain a mystery which I cannot answer, though long and hard have I thought upon it.

He was hungry and miserable, that is all there is to report of him. If he once many years ago had a Mother who loved him and held him to her breast and looked on his face as if it were the Treasure and the Wonder of the Age, as your Mother does with you, this I do not know. If he once had many friends or sweethearts, and was known as an honest and hard-working neighbor, these things also I do not know. Now he had no friend, no sweetheart, and was no one's neighbor. His closest relations these days were soldiers of the Caliph's guard, and he always fled down an alley when he saw them turn the corner and approach.

What troubles had led him to his present miserable and hopeless state, this also must be a story for some other night. They may have been troubles of his own making, or they may just as easily have sprung from some undeserved injustice. Tonight, Dear Child, your Father knoweth not.

I know this, though: The beggar's name was Shakashik. And that is the last time I shall say it. For the first thing all beggars, vagrants, street people, prisoners and petty criminals lose is their names.

And the first thing they acquire is suspicion, a gift generously bestowed upon them by the prosperous who cringe from them every day in the marketplace or the public parks and squares.

So his most natural instinct, when suddenly confronted by what seemed to him a Miracle, was suspicion. A fat man, dressed in marvelously colored satins and silks, in wondrous fancy curley-toed shoes, with the magnificent feather of some poor dead bird sticking out of his magnificent turban, walked straight up to the beggar, took hold of his shoulder with his right hand, and his gnarly naked elbow with his left hand, and with a huge, radiant smile, spoke to the beggar.

"Brother," he said, "the hour when my household sups is upon us. Be kind, Brother, and cure my sadness that, without you, I must sup alone. Come inside with me now, share my repast, let us feast and praise Allah for His bounty!"

The beggar's mind and heart debated, but his empty belly commanded, and he gave no further resistance to the tug through the entrance gate of what proved to be a fine garden leading by a winding path of fine stones to a rich, imposing mansion. By the fat man's brilliant raiment, the beggar knew him to be a Barmecide, a member of a prosperous Brotherhood known widely for generosity and civic gifts. So even his suspicious mind began to worry a bit less, as his belly prepared to receive solid food from a kitchen rather than a garbage pail in an alley.

The Barmecide led the beggar through a great door, through a great entrance hall lined with delicate pillars of pink marble, to a fine winding stairway to the second storey of the mansion, down a hallway, and finally, through one more door, to a rich chamber illuminated against the setting sun by hanging brass lanterns. In the center of the chamber was a great round brass dining tray, surrounded by plush, comfortable pillows and cushions, and it was upon the fattest and softest of these that the Barmecide bade the beggar sit. When he had done so, the Barmecide sat upon a fine, fat satin pillow across the dining tray from the beggar, and then with relish and enthusiasm for the feast ahead, clapped his hands together sharply.

Instantly a servant entered the chamber bearing a small tray with fine brass bowls of sweetly perfumed water, and hovered discreetly as the Master and his not overclean Guest washed their hands. Then the servant vanished, but instantly another took his place, with a bigger tray, with the finest crystal pitcher and two matching crystal goblets. Had the beggar been a thief (he was not, this I know of him), these crystal objects alone, he knew immediately, would buy him a month of leisure, pleasure and full bellies.

The servant vanished, and the Barmecide, his generous smile widening, filled both glasses from the pitcher. But the chamber just after sunset was yet a bit dim and dark, it was hard to see all, and the beggar's natural suspicion returned.

Could it be? he asked himself ... and he took his glass, and his suspicion was confirmed. The rich crystal pitcher had held air, and his glass, and the Barmecide's glass, too, held naught but air.

"Wine, forbidden us by the Prophet -- but toast the Prophet and Allah with me, my Brother, nevertheless! Surely Paradise will not be denied either of us for this smallest and most mysterious of sins. Toast with me, my Brother, with this tiny sample of what will surely not be denied us in Paradise!" And he clinked his empty goblet against the beggar's goblet, and the Barmecide downed every last drop of Nothing, and wiped his lips with his satin napkin, as if it had been the finest wine from Muscat.

Nervously, the beggar imitated his Host's mime.

Another clap from the Barmecide, and another servant entered the chamber with yet a larger tray, this one with six silver serving bowls, each covered with silver tops. (A year of leisure and pleasure if the beggar had been a thief.) With great and elaborate silver ladles, the Barmecide scooped rich heaps of air upon two silver plates, then handed one plate of nothing to the beggar, and waited with great anticipation for his Guest to scoop up the wonderful nothing with his right hand and fill his mouth before the Barmecide would taste the puzzling riches from his own empty plate.

The beggar nervously scooped air with his right hand and filled his mouth with air. The Barmecide leaned forward and stared politely into his Guest's face. Nervously the beggar smiled a bit. Out of his confusion and suspicion, he said:

"Delicious!"

and tried his best to smile. The Barmecide, who had waited patiently, now scooped air into his own mouth with relish and gusto, making all the familiar sounds of a man who loves to eat and doesn't mind showing it to others at the table.

For the next half-hour the strange ritual was repeated again and again. The beggar eyed each new servant who brought each new brass tray filled with each new course of air in each new silver platter, but could find no clue from any servant's expression or demeanor that the servant was on any errand other than to bring the most delicious riches from the far corners of the World for his Master's guests to feast upon.

And the Barmecide himself -- his portion of the wonderful air clearly filled him ever more with satisfaction and delight. Whenever he noticed that the beggar's empty glass was empty, he grabbed the empty pitcher and poured more air into the beggar's glass, and then his own, and again they toasted the Prophet, and drank nothing.

In the beggar's mind, confusion was finally departing, and suspicion finally galloped to the lead in this strange race. The Barmecide was a wicked joker, a prankster. And the beggar was tonight's dupe and fool. He had been chosen from off the pavement for one obvious virtue alone: He was starving. Without that, the fat, cruel old Barmecide could not have his laugh and his joke.

The beggar could have just stood up and stalked off in angry muttering -- no crime in that, no trouble could possibly ensue even if the Caliph's guards were waiting at the Barmecide's gate.

But he called upon his wit -- he had a bit of that remaining, though his anger was trying to hide it from him -- and smiled broadly at his Host, revealing all his remaining teeth, and reached for the crystal pitcher.

"Most Generous Host in all Baghdad, you have let your glass stand empty," he smiled, and filled it up, and filled his own up, and they clinked glasses and toasted the Prophet again.

Now the reason Allah in His Wisdom forbade us wine was the universally evil effects it has on the best of men and women who drink it to excess.

And surely they are not to be blamed for what comes next; they are drowning in the grip of Satan's alcohol. The beggar had been there. The beggar had done that.

He noticed again his Host's empty goblet, he noticed his own thirst, and he refilled the glasses, they toasted, they drank nothing. And again. And again. And again.

Suddenly, speaking like a drunken clown, with his words slurred, the beggar jumped to his feet, and in a seizure of drunken violence, smashed his fist into his Host's face, knocking him backwards onto the floor, in shock and pain.

And surely he was not to be blamed for what he had done; he was drowning in the grip of Satan's invisible alcohol.

Now it was the Barmecide's turn to be confused and suspicious -- and afraid.

But that took no more than five seconds. He sat upright, reached for his knocked-away turban, tried to restore his rich clothing to some semblence of dignity.

And then he laughed -- this time a truthful, loud laugh from the heart.

"Forgive me, Brother! You have found my wicked jest out, and you have had not just your wine, but your revenge!"

Then he clapped the loudest clap of the evening. Instantly more servants, one, two, three, four of them, each bearing more brass trays, more silver platters with silver tops. But this time, if the bowls contained air, it was air fragrant with wonderful smells of true delicious food. The beggar's nostrils remembered roasted lamb, and garlic, and leeks, and steamed dates, ground black pepper and rosemary. His nose recognized a dozen memories of better times.

A fifth servant followed, his tray bearing an even bigger crystal pitcher, and this time filled with liquid with an unmistakeable rich amber hue. The Barmecide forced the beggar to sit again, and poured. They toasted the Prophet and the Bounty of Allah's World.

And long into the night they ate of wonderful dishes that never seemed to end, and toasted more, and laughed, and learned of one another's lives. Two happier men there never were, and when they could no longer keep their eyes open, the Barmecide and his servants showed the beggar to a rich sleeping chamber and put him to bed. When he awoke, there awaited the beggar a new and very fine suit of clothes, new shoes, and a fine turban.

And a genuine Miracle, not a Miracle of empty air, occurred. The Barmecide and the beggar became friends. The gave Salaam to one another whenever they met, and no matter how humble the beggar's conditions, the Barmecide crossed the street to do him Greeting, ask after his health -- and not infrequently, invite him to his mansion to sup food the beggar could taste and beverage he could swallow.

And this is the truth, Dear Child: The beggar and the Barmecide remained the best of friends forever after, until there came the Shatterer of All Loves, the Destroyer of All Friendships.

5 Comments:

Thanks Bob!

This is going to be my students' homework for next week :) I made them read the story, and i hope they'll leave comments.

Obrigado!

The Cook's Reward is truly wonderful (cf. "Babbette's Feast" by Dinesen)! But the Storyteller's Reward is just as sweet!

If your students like it but DO NOT Leave a Comment, let me know what they said!

Bob:

Thanks for the reminder of earlier days serving Sausage Spectacular to the homeless of Northampton in the Parish Hall of First Churches. Those were fine days...I hope we made some folks lives a little better for the inadequate amenities we were able to provide on the coldest nights.

hey first i wrote ten years then i thought better and wrote fifteen years ... my Sense Of the Passage of Time is totally unreliable. When was the first winter of the First Churches shelter? Lord know you should have some way of remembering that.

Lets see.

I was still living on Graves Ave, so I must have still been a student at UMass. I graduated in '93 with my undergrad, and lived there two more years. So, the first year that you and I worked the Shelter must have been winter of '92....almost 15 years ago.

Post a Comment

<< Home