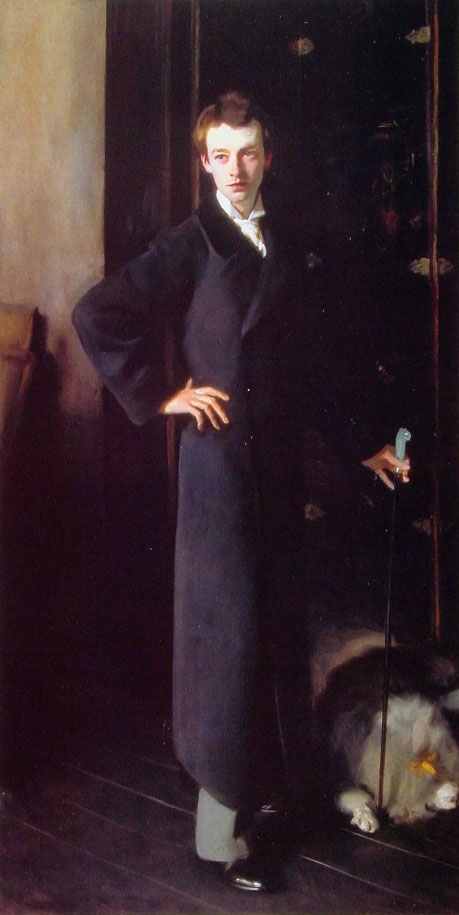

W. Graham Robertson, who gave Blake's "Newton" to the Tate (by John Singer Sargent)

W. Graham Robertson

W. Graham Robertson John Singer Sargent -- American painter

1894

Oil on canvas

Tate Gallery,London

Oil on canvas

230.5 x 118.7 cm (90-3/4 x 46-3/4 in.)

Jpg: Art Renewal Center

W. (Walford) Graham Robertson (1866-1948) was a gentleman artist. Born in London from a wealthy family he eventually dabbled in many forms and styles starting from Pre-Raphaelite oils to illustrations, caricatures, to portraits, later impressionistic landscapes, as well as being a talented writer. He was deeply interested in the theater and by the age of thirty had designed costumes for five major plays of which he received praise. He also painted many portraits of his friends and the leading actresses of the time.

He studied under Albert Moore (a Classical / Pre-Raphael painter 1841-1893) after first attending the South Kensington school.

Although he showed a lot of talent, he apparently never stayed with anything for very long. It seemed the art-form he was best at was the art of Schmoozing. He reveled in moving within social circles, was good friends with Burne-Jones and avidly collected Pre-Raphael art. By the time Sargent paints him as a London dandy -- he pretty much hits the nail on the head.

When John asked him why he had never painted a self-portrait, Graham responded, "Because I am not my style."

It's my impression that Graham liked to think of himself as the English equivalent of the Comte Robert de Montesquiou, whom he was also friends. Though, from what I can tell, Graham was far more talented, wielded far less influence, and didn't possess near the malicious streak (if at all) that Montesquiou had.

The painting took place in Sargent's studio and John insisted on the long fur-collared coat, jade handled cane, and Graham's own dog as props. Graham was 28 years old at the time, though the boyish face and frame made him look much younger. When Graham complained about the heat (since it was summer) Sargent persisted that the coat, itself, was the painting.

The following is an excerpt from Graham's autobiography "Time Was":

(page 2 of 2)

"Time Was: the reminiscences of W. Graham Robertson"

1931

Excerpts relating to John Singer Sargent -- pp.233-244

In 1894 I blossomed into a Notable Personage myself: it was a second-hand notability, a reflected aureole but distinctly noticeable. I dined out in it for a couple of seasons, and even now it sheds an occasional glimmer upon an otherwise unillumined name. More or less by accident, I became the subject of one of John Sargent's most famous pictures.

Sargent was still a young man (nobody was very old in the early 'nineties), and Tite Street, Chelsea, did not as yet show the un-ending procession on its way to his studio that thronged it in later days [pic], but several distinguished clients had already passed that way and, as Oscar Wilde observed to me, "The street that on a wet and dreary morning has vouchsafed the vision of Lady Macbeth in full regalia magnificently seated in a four-wheeler can never again be as other streets: it must always be full of wonderful possibilities [pic]."

Sargent's fame was approaching its zenith, though sitters were still a little coy: his portraits were not always quite what the subjects expected -- they could not feel comfortably certain of what they were going to get.

"It is positively dangerous to sit to Sargent. It's taking your face in your hands," said a timid aspirant; and many stood shivering on the brink waiting for more adventurous spirits to make the plunge.

This was Sargent's great period, when he was not so over tasked with commissions and was able to concentrate upon the work in hand.

I had long wanted a portrait of my mother and was lucky in persuading him to undertake it, though it was perhaps not a complete success [Mrs. Graham Moore Robertson]. My mother was a bad sitter, she was shy and very loath, as she expressed it, to 'sit still and be stared at.'

Sargent could not reproduce her real self because during the sittings he never saw it, although afterwards they became good friends. Still, the portrait was a fine piece of work and a brilliant superficial likeness.

I was often commandeered to attend the séances, as my mother required support (and considered that the casual woman friend worried the artist, in which opinion she was not far wrong.

Ada Rehan

Ada Rehan [pic] was sitting to Sargent at the same time, a large portrait of her having been commissioned by an American adorer, one, Mrs. Whiting of Whitingsville, Mass. I remember the imposing name, as it seemed to fascinate Sargent, who became haunted by it and would chant it rhythmically as a kind of litany the while he painted, the 'Mass.' in very deep tones coming as a final Amen, in which I reverently joined.

Miss Rehan was another shy and reluctant sitter and, between the two, the poor artist must have had uphill work. Each, I think, found a certain comfort in the other's discomfort; they were comrades in misfortune and even shared certain studio "properties," Sargent borrowing from my mother her white feather fan for Ada to hold outspread while she glanced at the spectator over her shoulder.

The comic relief of the sittings was supplied by my dog, Mouton, who, well stricken in years and almost toothless, claimed rather unusual privileges and was always allowed one bite by Sargent, whom he unaccountably disliked, before work began.

"He has bitten me now," Sargent would remark mildly, "so we can go ahead."

Miss Rehan's sittings had been interrupted by a few final rehearsals of "Twelfth Night" before its production in London, but at last the evening arrived. I was "in front" with a friend, J.J. Shannon, then Sargent's most formidable rival among portrait painters, and had sent round a line to the Leading Lady asking to see her when all was over.

Almost from the start her Viola had enchanted the audience, but in the midst of her triumph, and success in a great Shakespearean role in Shakespeare's country meant very much to her, she found time to scribble a note and to send it to me.

Yes. come by all means. I have something particular to tell you about Sargent -- something he said of you -- you must hear it and, I hope, act upon it. Shall I tell you before your friend? -- you must bring him. This evening is so nice -- it has unnerved me a little.

Affectionately, ADA REHAN

I felt puzzled and intrigued. What could Sargent have said of me, Sargent who so very seldom said anything of anybody? It was quite exciting. We presented ourselves in due course and found Viola rather overwhelmed by her great ovation, but still eager to impart news.

"Well, he's very anxious to paint you."

"Me?"

"Yes. He wants you to sit to him?"

"Wants me? But good gracious, why?"

"I don't know," said Ada, a little tactlessly. "He says you are so paintable: that the lines of your long overcoat and -- and the dog -- and -- I can't quite remember what he said, but he was tremendously enthusiastic."

I did not wonder that Miss Rehan's memory had failed, but I was well able to supply the missing words. Sargent, I felt sure, had delivered himself thus -- "You know-there's a certain sort of--er--er--that is to say a kind of --er--er--in fact a--er--er____" and so on and so on. He had not the gift of tongues, but that mattered little; he was so well able to express himself otherwise.

Heraldic Sense

No one had ever wanted to paint me before. Portions of me had been borrowed from time to time; hands pretty frequently by Albert Moore, hands again by Poynter, quite a good deal by Walter Crane for immortals of uncertain shape and sex, but I myself, proper (I use the word in its heraldic sense [1]), had never been in request. Even now, as far as I could gather, the dog and the overcoat seemed to be regarded as my strong points; nevertheless, I felt very proud and -- well, Sargent soon had three large canvases on hand instead of two.

Being but an amateur model, I was easily entrapped into a trying pose, turning as if to walk away, with a general twist of the whole body and all the weight on one foot. Professional models will always try to poise the weight equally on both feet and will go to any lengths of duplicity to gain this end.

I managed pretty well on the whole, but the sittings cleared up a point which had long puzzled me: why did models occasionally faint during a long pose without mentioning that they felt tired and wanted a rest? One day the answer came to me quite suddenly. I had been standing for over an hour and saw no reason why I should not go on for another hour, when I became aware of what seemed a cold wind blowing in my face accompanied by a curious "going" at the knees.

I tried to ask for a rest, but found that my lips were frozen stiff and refused to move. Hundreds of years passed-- I suppose about twenty seconds.

Sargent glanced at me.

"What a horrid light there is just now," he remarked. "A sort of green-" He looked more steadily. "Why, it's you!" he cried, and seizing me by the collar, rushed me into the street, where he propped me up against the door-post. It was a pity that Oscar Wilde opposite was not looking out of the window: the "wonderful possibilities of Tite Street" were yet unexhausted.

Comte Robert de Montesquiou

After the picture was well advanced it was laid by for a short time while the artist took a holiday in Paris, and when I started sittings again I found him much perturbed.

"I say," he began, "did you ever see Whistler's portrait of Comte Robert de Montesquiou?[pic]"

"No," said I. "They never would let me see it while it was being painted. Why?"

"Well, I'd never seen it either," said Sargent, "until I came across it just now in the Champs de Mars. It's just like this! Everybody will say that I've copied it."

My old friend Robert de Montesquiou had been sitting to Whistler while Sargent's portrait of me was in progress, but had shrouded the fact in all the romantic secrecy that his soul loved.

He was in England incognito (I cannot imagine why) and took much delight in gliding down unfrequented ways and adopting strange aliases; visiting me by stealth after dusk with an agreeable suggestion of dark lanterns and disguise cloaks, though, as he was almost unknown in London, he might have walked at noon down Piccadilly accompanied by a brass band without anyone being much the wiser.

Whistler, who also loved to play at secrets, was equally clandestine, I, dutifully acting under orders, dissembled energetically, and Montesquiou was so wrapped about in thick mystery that no intelligent acquaintance within the three miles radius could possibly have failed to notice him.

And now the mystic portrait was on view in Paris, and Sargent had found it just like mine and feared that critics would agree with him.

[See Montesquiou in Juxtaposition]

And in truth a few people did make the remark, though there was really but little resemblance. Both canvases showed a tall, thin figure in black against a dark background, but the likeness ceased there and, as a picture, the Sargent was by far the finer. The Whistler was not of his best -- the blacks were black, not the lovely vaporous dimness of the "Rosa Corder"; the portrait was quite worthy neither of the painter nor the model, for the delicate moulding of Robert de Montesquiou's features was hardly suggested; but Whistler was not then quite equal to the physical exertion of dealing with so large a canvas. He had started two portraits of Comte Robert, working upon them alternately, but as far as I know only one survived: it was the last large picture that he ever completed.

The Sargent, on the other hand, was of the artist's best period and he was painting something that he had "seen" pictorially and for some unknown reason had wished to perpetuate. Why a very thin boy (I then looked no more) in a very tight coat should have struck him as a subject worthy of treatment I never discovered, but he evidently had the finished picture in his mind from the first and started it almost exactly upon its final lines. It was hot summer weather and I feebly rebelled against the thick overcoat.

"But the coat is the picture," said Sargent.

"You must wear it."

"Then I can't wear anything else," I cried in despair, and with the sacrifice of most of my wardrobe I became thinner and thinner, much to the satisfaction of the artist, who used to pull and drag the unfortunate coat more and more closely round me until it might have been draping a lamp-post.

Even before the picture was finished its fame began to grow, and friends took to dropping in, anxious for a sight of it. Sargent's old friend, Henry James, whom I had known before very slightly, came several times and expressed high approbation.

Henry James

The Henry James of those days was strangely unlike the remarkable-looking man of almost twenty years later, who was then himself painted by Sargent [pic].

In the 'nineties he was in appearance almost remarkably unremarkable; his face might have been anybody's face; it was as though, when looking round for a face, he had been able to find nothing to his taste and had been obliged to put up with a ready-made "stock" article until something more suitable could be made to order expressly for him.

This special and only genuine Henry James's face was not "delivered" until he was a comparatively old man, so that for the greater part of his life he went about in disguise.

My mother, who was devoted to his works, used to be especially annoyed by this elusive personality.

"I always want so much to talk with him," she complained, "yet when I meet him I never can remember who he is."

Perhaps to make up for this indistinguishable presence he cultivated impressiveness of manner and great preciosity of speech.

He had a way of leaving a dinner-party early with an air of preoccupation that was very intriguing.

"He always does it," untruthfully exclaimed a deserted and slightly piqued hostess. "It is to convey the suggestion that he has an appointment with a Russian princess."

In later life both the impressive manner and fastidious speech became intensified: what he said was always interesting, but he took so long to say it that one felt a growing conviction that he was not for a moment, but for all time. With him it was a moral obligation to find the mot juste [3], and if it had got mislaid or was far to seek, the world had to stand still until it turned up.

Sometimes when it arrived it was delightfully unexpected. I remember in later years walking with him round my little Surrey garden and manoeuvering him to a spot where a rather wonderful view suddenly revealed itself.

"My dear boy," exclaimed Henry James grasping my arm. "How--er--how_____" I waited breathless: the mot juste was on its way; at least I should hear the perfect and final summing up of my countryside's loveliness. "How--er--how______" still said Mr. James, until at long last the golden sentence sprang complete from his lips. "'My dear boy, how awfully jolly!"

I also recall his telling of a tale about an American business man who had bought a large picture.

"And when he got it home," continued Mr. James, "he did not know what---er----

what______"

"What to do with it," prompted some impatient and irreverent person.

Henry James silently rejected the suggestion. "He did not know what---er--what-- well, in point of fact, the hell to do with it."

When, quite towards the end of his life, his new face was evolved, it was a very wonderful one and well worth waiting for. Sargent's painting of it is fine, but lacks a certain something.

"It is the sort of portrait one would paint of Henry James if one had sat opposite to him twice in a bus," said a disappointed admirer, and the statement, though untrue, had some grains of truth in it.

Yet this should not have been so. Sargent and Henry James were real friends, they understood each other perfectly and their points of view were in many ways identical.

Renegade Americans both, each did his best to love his country and failed far more signally than does the average Englishman: they were plus Anglais que les Anglais [4] with an added fastidiousness, a mental remoteness that was not English.

Both were fond of society, though neither seemed altogether at one with it: Henry James, an artist in words, liked to talk and in order to talk there must be someone to talk to, but Sargent talked little and with an effort; why he "went everywhere" night after night often puzzled me.

I saw a good deal of Henry James at about this time, then we lost sight of each other for many years. When I next met him, almost unrecognisable in his new face, he seemed much aged and broken. His ever troublesome nerves had now made him more dependent upon companionship; some of the mystery and remoteness had disappeared.

His final nationalisation as an Englishman [in 1915] came as a surprise to many. His liaison with Britannia was then such an old story, both had completely lived down any scandal, and that he should wish at the eleventh hour to make an honest woman of her seemed almost unnecessary.

His portrait by Sargent [pic], one of the few men who really knew him, should have supplied a clue to the true Henry James that no one else could have found: perhaps the artist intentionally withheld it.

Sarah Bernhardt

Another friend who volunteered to "come and sit with me while I was being painted" (how painters of portraits have learned to dread that offer) was Sarah Bernhardt [pic].

She wished to see what Sargent was "making of me" and proposed her chaperonage at an early stage of the portrait's evolution.

I had misgivings; I could not see Madame Sarah sitting quietly in a comer while I basked in the limelight.

"But it will bore you," I ventured.

"No," said Madame Sarah. "I want to see the picture and I'm coming. You must call for me and take me with you."

"But the sitting is early: you will never get up in time and you'll never be ready."

"I shall get up and I shall be ready. I am coming," said Sarah with finality; so of course she came.

If the sun had risen in the west that morning it would have surprised me less than the sight of Madame Sarah ready and waiting when I called for her at an early hour, waiting in a neat, business-like walking-dress with a small black hat. She might have been going to shop at Whitely's with a string bag.

Sargent, who disliked the flamboyant type of actress, was completely won over and surveyed the little dark figure with approbation.

"I never saw that she was beautiful before," he whispered to me. "Look at her now."

Sarah was leaning forward, getting a view of the picture in a little hanging mirror: she was poised, the tips of the fingers against the wall, the head thrown back, the delicate profile in relief against a black screen.

I believe that Sargent only narrowly escaped asking to paint her then and there, but that he did escape was perhaps fortunate. They were not sympathetic; Sargent as a painter of Facts was unrivalled, but Sarah Bernhardt was embodied Fantasy and was only well and truly seen through the golden mist of dreams. Dreams were not in Sargent's line.

Ellen Terry

The Ellen Terry portrait [pic], imaginative and dramatic, was a splendid exception to this rule; here, I think, the magnificent pomp of colour had fired the artist's fancy, but in the head of Henry Irving, painted in the same year, he had again shown his limitations.

He had painted the great actor with the flame of his genius blown out and had shown that the marvellous face, had it belonged to someone else, might not have been marvellous at all.

Here was a face that might look drearily at us out of a ticket office or haughtily take our order for fancy trouserings; it might bend over a ledger with a pen behind its ear or stare in listless apathy at small children in a Board School, but never could it blaze like a beacon or lower like a thundercloud, never could it have held crowds spellbound and swayed them with a glance. It was not Henry Irving, but the dreadful thing about it was that it might have been, and the sitter, probably recognising this, actively hated it.

He hid it away for some time, but one morning when it shyly peeped from the boot cupboard or crept from under the bed, he took a breakfast knife and__________ There is now no portrait of Irving by Sargent. . .

His destruction of the Sargent portrait was of course regarded as a great crime, and it was perhaps as well that Sarah Bernhardt [pic] was not exposed to a like temptation.

I wonder whether, having us both before him in his studio, Sargent noticed that, all unlikely as it sounds, there was then a vague resemblance between Madame Sarah and myself.

She had apparently realized it before I did. I had paid a sudden visit to Paris without advising her of my advent and had, as usual, gone on my first evening to see her play. When I went round to her dressing-room after the fall of the curtain I found her expecting me.

"But I never told you that I was coming."

"No," said she, "but when I was on the stage one of the actors (he's new and does not know my friends) whispered to me, 'Your son is in the audience, Madame Sarah'; and when I said, 'But you have never seen Maurice,' he told me that he recognized him from his likeness to me. Now Maurice is not in the least like me, so I felt sure that it must be you."

"But I am not like you," I said, all incredulous.

"Look," said Sarah, and leading me to the mirror she put her face beside mine.

It could not be denied that there was a certain sort of something, as Sargent would have said, a blurred travesty of her clear-cut face; but, had I been Madame Sarah, I should I not have mentioned it. That she should contrive to resemble the Mona Lisa of Leonardo and the Primavera of Botticelli and also to be rather like me was perhaps one of her most amazing feats.

My face acquired for me a spurious interest for some time after-which reminds me that while I was sitting to Sargent I made a joke.

I know it was a joke because several people laughed at it and it gained me quite a little reputation, but it must have been very subtle, as I have never been able to grasp the point a myself.

Sargent had asked me why I had not painted myself and I replied, "Because I am not my style." That was the joke.

Sargent didn't see it until three days afterwards, when he suddenly burst out laughing at a dinner at Sir George Lewis's [pic]. That was the birth of the joke as a joke. It had a great success; it went the round of the studios, it was translated into French by Mr. George Moore and the translation revised and reedited by Walter Sickert. When the latter repeated it to me in its final form I almost saw it, but the illumination was only momentary. I can't see that joke yet; in fact, I don't believe that it is a joke.

Sargent's studio parties

Sometimes Sargent would give studio parties at which the originals of the various portraits would prowl suspiciously round each other, perforce paying tribute to rival charms, yet each comfortably confident that he (or perhaps in this case mostly she) was sole possessor of the elusive quality-the "certain sort of a something"-that drew out the. greatest powers of the painter.

Once we were summoned to meet and admire Carmencita [pic], the dancer, whose portrait had been one of the first of Sargent's sensational successes. This was to be an unusually large gathering and the artist was rather puzzled by questions of space: the dancer and her guitar players required about half the studio for their evolutions; there was not much room for an audience. Sargent was the kindliest of men; unless really roused, it was very difficult for him to say No: the invitation list presented a troublesome problem.

"I suppose I must ask So-and-So," said Sargent dismally.

"Why should you?" I demanded.

"Oh, well, you know-I suppose-I ought to."

"But do you want to?"

"No," said Sargent with unusual firmness.

"Then don't."

"All right," said Sargent bravely, as he scratched out the name. "I won't. I'm-I'm damned if I do."

Nevertheless, when I arrived at the party, the first person I met was So-and-So.

The scene in the dimly lit studio was a Sargent picture [pic] or an etching by Goya, the dancer, short-skirted and tinsel-decked, against a huge black screen, the guitaristi, black against black, their white shirts gleaming. And then Carmencita danced. She postured and paced, she ogled, she flashed her eyes and her teeth, she was industriously Spanish in the Parisian and American manner, she looked beautiful and tawdry, but she was not a great dancer -- it was all a little disappointing. Then she retired, to reappear in a dress of dead white falling to her feet, with a long, heavy train; she wore no jewels, only one dark red rose behind the ear. And she sang the wild, crooning "Paloma," and as she sang she circled with splendid arm movements, the feet hardly stirring, the white train sweeping and swinging round her. This was better-this was different. This was not Carmencita of the Halls, but the real dancer of Old Spain.

Then Sargent came to her whispering a request. She looked angry, then sullen, shaking her head violently. He persisted, and opening a great cupboard in the wall, held out to her a beautiful white shawl with long fringes.

She still hesitated, pouting, then snatched the shawl, threw it over her shoulders, flicking him in the face with the fringe with the impudent gesture of a gamin, and slowly crouched down upon a low stool, her face now grave, her hands in her lap. From the guitaristi behind her came a low thrumming, a mere murmur, and softly, under her breath, Carmencita began to sing.

Old folk songs she sang, mournful, haunting, with long cadences and strange intervals, and as she sang she clapped her hands, softly swaying to the rhythm. And her beauty changed, the tawdriness fell away, she became ageless and eternal like the still figures of Egyptian sculpture.

She was one with the "spinsters and the knitters in the sun" who crooned and swayed thus while the Moors were building the Alhambra, nay, perhaps when Nimrod was building Nineveh.

Sargent told me afterwards that she had held out long against the performance. It was low, she declared; the common people sang these songs at street corners -- they were not for Carmencita of Broadway and the Boulevards; what would his fine ladies and gentlemen think of her if she thus forgot herself?

But those whispered lilts laid a spell upon her audience, and the name of Carmencita now brings me no vision of a pirouetting dancer, but memory of a quiet, shrouded figure with darkly dreaming eyes and hands rhythmically clapping.

I wonder that Sargent had not chosen to paint her thus rather than in her short-skirted finery [pic]; I suppose it was because he had already used the white satin and long train motif in one of his best early pictures, El Jaleo.

* * *

Notes

Special thanks to Kathie Roskom, a friend of the JSS Gallery, for help on the excerpt from Graham's autobiography

Natasha Wallace

Copyright 1998-2005 all rights reserved

Created 1/14/2003

Updated 4/10/2005

Puppet Shows

Puppet Shows

3 Comments:

I am in London and just saw this painting today (Feb. 25th).

Marvelous painting. A friend used the Newton on the cover of his book (legal philosophy).

Jay

I am consumed with envy. Have a great time! Send Vleeptron back a travelog -- snapshot of visiting London right now. Have you seen a Flash Mob?

I really liked his memoirs; he was hanging with The Greats of The Moment.

If you read this, check out Sargent's huge war painting "Gassed" at the Imperial War Museum in Lambeth. All I hear about the IWM says it's spectacular, but "Gassed" is considered to be one of the great war paintings of all time.

Other museums I've had a great time at in London are the Victoria and Albert, the Science Museum (Babbage's circa 1870 brass and steel and clockwork gear digital computer is there, and the damn thing works!), and my very fave place on the planet, The Old Royal Observatory at Greenwich. And that's just a mile up the river from The Thames Barrier, a really awesome Thang.

Oh yeah and you might want to check out Kelmscott House.

Post a Comment

<< Home