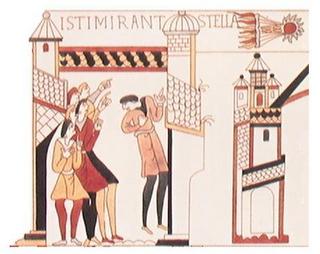

Comet Halley before the Battle of Hastings (1066)

A panel of the Bayeux Tapestry (actually an embroidery), a history (from the winner's viewpoint) of the successful invasion and conquest of England by William of Normandy in 1066. Here men of William's Court -- probably meant to be astrologers -- gaze at a strange new star in the night sky, which we know today to have been Comet Halley (which returns to Earth's neighborhood about once every 76.3 years). They interpret it to be a portent for William's success in the invasion.

Despite a clear realism, the art precedes the introduction of perspective (a technique invented by the Arabs); here and until about the 13th century, size implies importance, and is not used to fool the eye into believing it is seeing a 3-dimensional world.

In Simon Schama's "A History of Britain," the historian focuses on another Bayeux panel -- the first depiction (but not the last) in European art of war's refugees, a mother and child fleeing from their house from William's invading army. In official art commissioned by the wealthy and powerful to commemorate great men and great events, it is very rare for the artist's eye to stray from the great men to ordinary, nameless people; it is very rare for the artist to ask us to take note, however briefly, of the pain, dread, panic and fear of civilians.

In art and in the chronicles, the plight of refugees -- it is almost never even noticed, it is taken for granted, the mass dislocation and deprivation and suffering of tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions of children, women, old men, taking to the roads, fleeing for their lives, fire and sword just behind them. Very often war leaves a huge mess behind and normal lives do not just promptly resume after the regime change. In Southeast Asia, in Africa, in Central Asia, in the Middle East, entire generations grow up in refugee camps in squalor and deprivation unimaginable in the West, where we take stability, safety and bounty for granted. Refugee camps, where people have lost everything, where there is no hope for a better future, are the breeding grounds of the terrorists we fear most in the West. While so much of Asia and Africa live this way permanently, we can expect the subnational violence we have taken to call terrorism -- not so much a description of the phenomenon, but a judgmental condemnation of it, our Western opinion that they should stop because all decent people know it's not a nice or decent thing.

2 Comments:

Indeed. And again I can't help quoting from Tony Kushner's lovely poem «An Undoing world»:

...A refugee who's running from the wars,

Hiding from the fire-bombs they've hurled;

Eternally a stranger out-of-doors,

Desperate in this undoing world.

http://service.spiegel.de/cache/international/0,1518,341230,00.html

... an excerpt from Victor Klemperer's diary account of the firebombing of Dresden, from the German magazine der Spiegel's English on-line service.

Post a Comment

<< Home